Strategies to Promote Women

To assess how organizations can advance more women into leadership roles, WLI developed and tested a model that distinguishes among the different approaches organizations can take.

Survey respondents were asked to rate experiences that have been most important to their development and career advancement and rank those they expect to be most important in the future.

WLI Research Model

Formal approaches, which are more policy or program driven, include training, development, and human resources practices that range from objective hiring, promotion, and performance-evaluation policies to workplace flexibility and family leave.

Informal approaches are woven into daily work, such as job assignments, workplace culture, the network of relationships inside and outside organizations, ongoing coaching from managers, and sponsorship by senior leaders.

While these approaches support both men and women in their careers, this study is particularly interested in learning which approaches women have found most valuable.

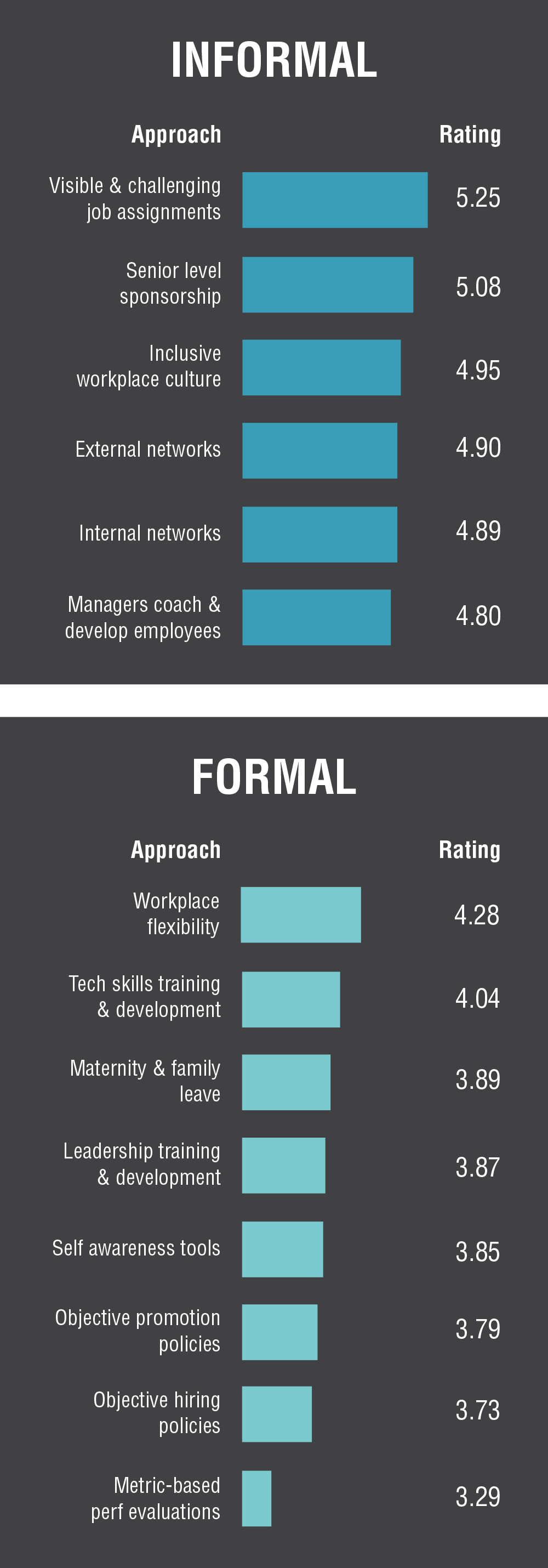

Rating of Past Experiences

After determining which approaches were most valuable to women in their careers so far, WLI grouped them into eight categories and asked women to rank the items in terms of importance for their future in the industry. This analysis enabled WLI to identify priority actions that organizations can take to advance their female employees in a more equitable manner.

Priorities for Organizations Going Forward

WLI further explored the survey findings through focus groups and interviews.

On the whole, women are consistent in their opinion regarding the value of different approaches regardless of their current organizational level, career aspiration, satisfaction with pace of career advancement, organization size, generation, and industry.

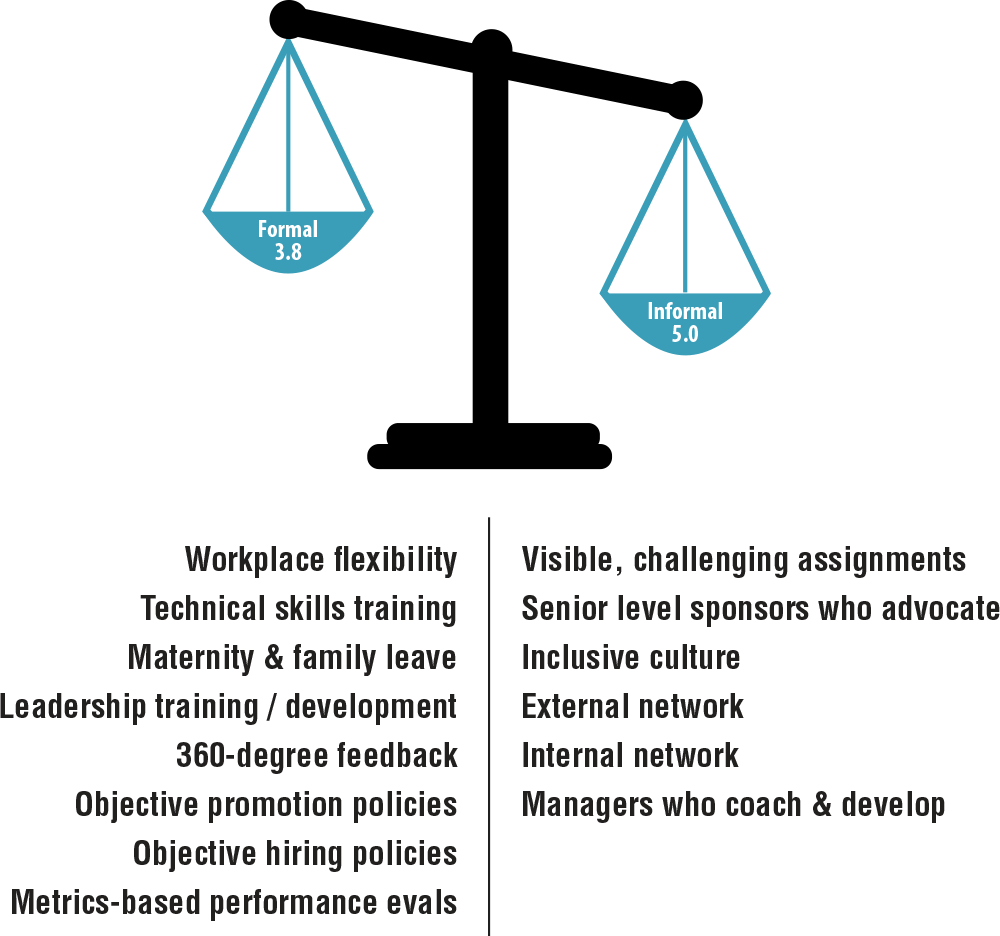

Challenging work assignments, an inclusive culture, and managers who coach matter more to aspiring female leaders than do formal women’s programs and training.

The survey reveals that informal approaches are deemed more important in terms of both past experiences and future priorities. The average rating for all informal approaches (5.0, or “very important”) was substantially higher than the average for all formal (3.8, just below “important”).

Women said that though valuable, policies and programs as stand-alone interventions are not as likely to effect change in the landscape for women.

Said one woman, “I don’t believe HR policies alone will change the pace at which women advance at my firm. It takes at least one very senior line leader to take a stand and encourage a different way of thinking and acting.”

The research indicates that the most valuable changes involve a combination of formal and informal approaches and start by changing how work gets done each day and supporting those changes with strong programs, policies, and practices.

The category “providing challenging and visible job assignments for women” stands out as the most valued approach to advancement, both in terms of past experience and future priorities. Women consider a challenging job assignment to be either remaining in a current position while taking on new projects or responsibilities, or moving to a permanent new position through a promotion or lateral transfer.

This approach was added to the WLI model in response to input from a national focus group that convened in May 2015. Participants were asked to identify the experiences that have most contributed to their development and career advancement. By far, the most common responses involved specific work assignments and projects where the women had met challenges that exceeded those they had tackled in the past. This category was further explored during subsequent focus groups and case studies.

“I failed to get the memo that I am supposed to be intimidated by a roomful of men.”

Women in the field consistently value visible job assignments where they are accountable for producing results: more than 40 percent ranked it as the top priority for organizations going forward, making it more than twice as popular as the second selection. Women in real estate development value these assignments more than any other industry group.

During focus groups, some women recalled that career-changing roles had come unexpectedly, such as when a boss or colleague departed. Although they probably would not have been promoted to the role without the unexpected change, they were able to take advantage of the opportunity, step in, and prove themselves to more senior leaders in their organizations.

A number of women were not afraid to push for the most challenging assignments in their organizations. “I failed to get the memo that I am supposed to be intimidated by a roomful of men,” said one female CEO.

Making sure women have these opportunities often takes a conscious effort on the part of senior leadership.

“Having senior-level sponsors within my organization who advocate for me” is rated second highest among past experiences that have led to success. Many women said the opportunity to take on a challenging new assignment was often the direct result of a sponsor who believed in her and was willing to persuade senior-level colleagues that she had the capabilities to be successful.

Sponsors and mentors encouraged these women to take on significant stretch assignments. Cheryl Sandberg mentions in her book Lean In that women are less likely than men to take on new roles when they have all the skills required for that role. Some of the women interviewed said they would not have taken on a stretch role unless urged to do so by a trusted senior-level mentor or sponsor.

One C-level woman shared her greatest career regret—turning down a job offer early in her career. “I was afraid to take on a more senior-level position in a new organization because I expected I would have some failures,” she said. “I chose to stay where I could safely succeed. What I know now is senior-level positions are inherently complex, and everyone makes mistakes. Part of what women need is self-confidence and to keep moving as you hit those inevitable bumps in the road. Wanting to be perfect and avoiding making mistakes gets in the way for too many women.”

A different C-level woman described how her boss provided coaching when she faced a similar challenge in a start-up organization. “My boss was tough,” she said. “He told me I needed to stop spending time regretting past mistakes. ‘That is part of doing business. Fix what you can and move on.’”

Women generally regarded as high performers—those with the highest aspirations and currently at senior levels—value job opportunities that push them to perform. Among those who aspire to reach the most senior level, C-suite or CEO, 86 percent found “visible and challenging job assignments” either very important or extremely important, compared with 65.8 percent of those aspiring to midlevel management. Among senior leaders currently in executive-level roles just below the CEO, 90.2 percent have found job assignments and senior-level sponsors very important or extremely important to their career—making this approach more important to this group than to women at any other level.

“He told me I needed to stop spending time regretting past mistakes. ‘That is part of doing business. Fix what you can and move on.’”

It appears that women with higher ambitions and more success are either deliberately seeking out or are being given both more job opportunities that push them to perform and more sponsorship along the way.

Furthermore, those whose careers are lagging expectations find that visible and challenging jog assignments, an inclusive workplace culture, and networks outside their organizations have been less important than do those who describe their careers either on track or ahead of schedule.

Women who engage in visible career experiences in a culture that is inclusive while also building external relationships are most likely to have a career that advances on pace with or ahead of expectations.

Two interesting trends involve differences between the generations. On one hand, members of generations X and Y find that managers who coach and develop are more important than do baby boomers or traditionalists (those born before 1946), perhaps because the younger generations have less experience in the working world and are looking for input from their managers.

In contrast, visible and challenging job assignments are most important to the traditionalists and baby boomers than to generations X and Y. One theory to explain this is that challenging job assignments were the most available avenue for development in the industry in the 1980s and 1990s, whereas those entering the workforce after 2000 are finding other ways to support their advancement. In keeping with the theory, the small group of traditionalists surveyed found that internal and external networks, as well as senior-level sponsors, more important than they were to any other generation.

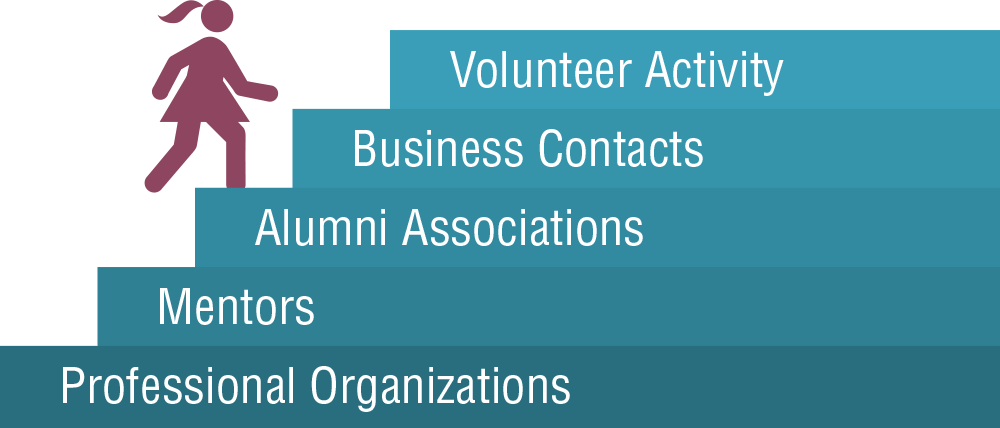

Female CEOs cite developing external networks as key to having advanced their careers and say it should be a top priority going forward.

Women CEOs place a higher value on external networks than do those at lower levels. Among CEOs surveyed, 77 percent rate external networks very or extremely important; among those in positions below the CEO level, 68 percent rate these networks as highly. For 20 percent of CEOs, opportunities to develop external networks are the first or second priority for the future.

Family leave, rather than maternity leave, is essential to employee satisfaction for both mothers and fathers.

The highest-rated formal approach to advancement of women is workplace flexibility, which includes flexible start and stop times, and other elements. Workplace flexibility was emphasized as a tangible sign that top leaders trust employees to manage their work to produce results.

As one would expect, workplace flexibility and “flexible or generous maternal, parental/family or elder care leave” are least important to baby boomers, most of whom are past the life stage of raising a family. Furthermore, workplace flexibility and family leave was ranked highest in importance going forward by millennials (22.4 percent ranking it first or second), followed by gen Xers (20.7 percent ranking it first or second); many members of these groups are at a life stage where starting and raising a family are front and center.

Creation of an inclusive culture where women thrive includes developing strong internal and external networks and employing objective hiring and promotion policies.

A correlation among approaches to advancement of women helps clarify the components that constitute an inclusive culture. Those who ranked “creating a culture that is inclusive” as very important for organizations going forward were also highly likely to rate the following as important in their own development:

- relationships/network inside my organization (role models, mentors, peers);

- relationships/network outside my organization (colleagues, customers, trade associations);

- objective promotion policies and practices; and

- objective hiring policies and practices.

Among formal approaches, an interesting distinction exists in that senior leaders currently at the C level rate objective hiring and promotion policies and practices as more important to their careers so far than do those at any other level.

It is possible that these senior leaders are in the best position to view the impact of these decisions because they are involved in both hiring and promotion decisions. On the other hand, CEOs control promotion and hiring processes and may be less able to critique them, while those below the C level are unlikely to see how the hiring and promotion decisions are made. Members of generations X and Y also found objective hiring policies and practices less important than they are to other groups, perhaps because their assumption, based on their life experience, is that hiring is a fair process.